Apache Hudi 1.1 Deep Dive: Async Instant Time Generation for Flink Writers

This blog was translated from the original blog in Chinese.

Background

Before the Hudi 1.1 release, in order to guarantee the exactly-once semantics of the Hudi Flink sink, a new instant could only be generated after the previous instant was successfully committed to Hudi. During this period, Flink writers had to block and wait. Starting from Hudi 1.1, we introduce a new asynchronous instant generation mechanism for Flink writers. This approach allows writers to request the next instant even before the previous one has been committed successfully. At the same time, it still ensures the ordering and consistency of multi-transaction commits. In the following sections, we will first briefly introduce some of Hudi's basic concepts, and then dive into the details of asynchronous instant time generation.

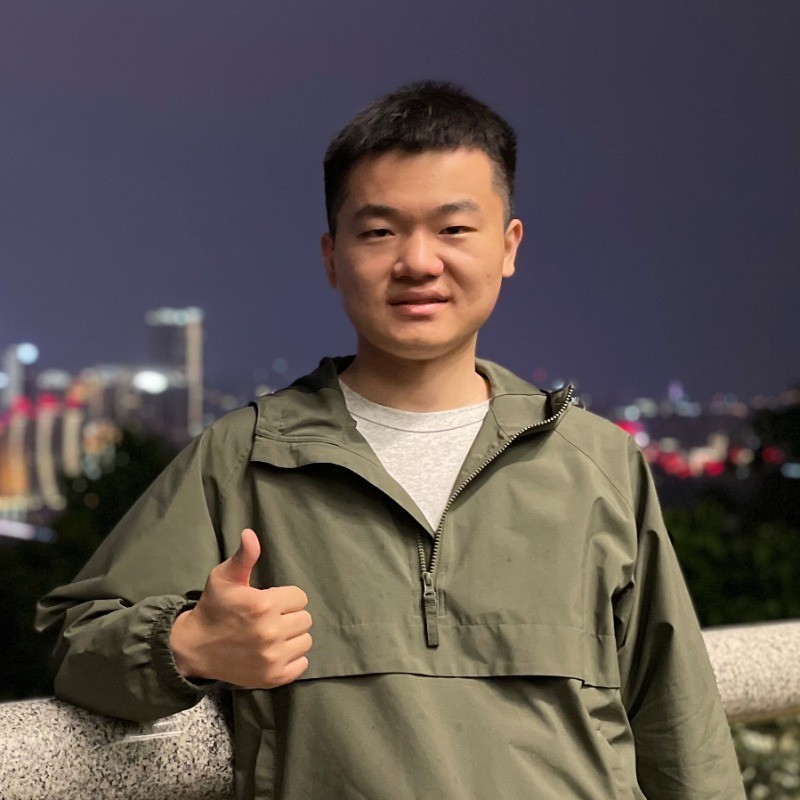

Instant Time

Timeline is a core component of Hudi's architecture. It serves as the single source of truth for the table's state, recording all operations performed on a table. Each operation is identified by a commit with a monotonically increasing instant time, which indicates the start time of each transaction.

Hudi provides the following capabilities based on instant time:

- More efficient write rollbacks: Each Hudi commit corresponds to an instant time. The instant timestamp can be used to quickly locate files affected by failed writes.

- File name-based file slicing: Since instant time is encoded into file names, Hudi can efficiently perform file slicing across different versions of files within a table.

- Incremental queries: Each row in a Hudi table carries a

_hoodie_commit_timemetadata field. This allows incremental queries at any point in the timeline, even when full compaction or cleaning services are running asynchronously.

Completion Time

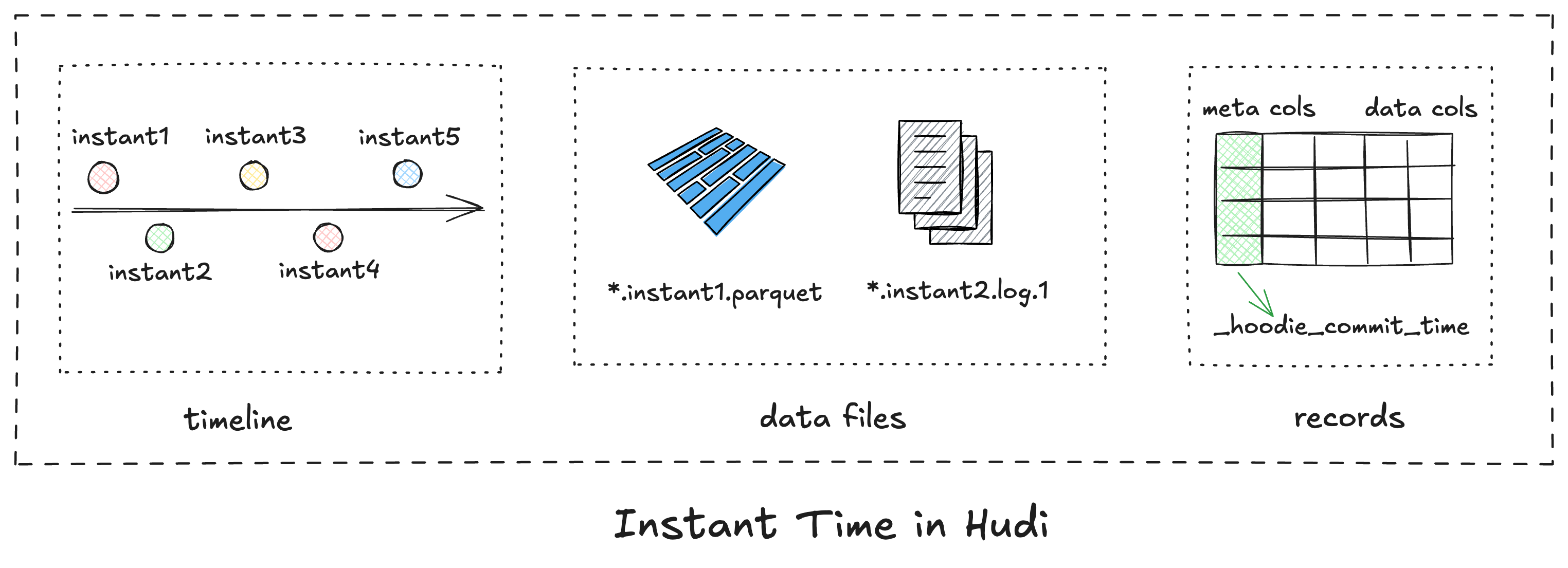

File Slicing Based on Instant Time

Before release 1.0, Hudi organized data files in units called FileGroup. Each file group contains multiple FileSlices. Each file slice contains one base file and multiple log files. Every compaction on a file group generates a new file slice. The timestamp in the base file name corresponds to the instant time of the compaction operation that wrote the file. The timestamp in the log file name is the same as the base instant time of the current file slice. Data files with the same instant time belong to the same file slice.

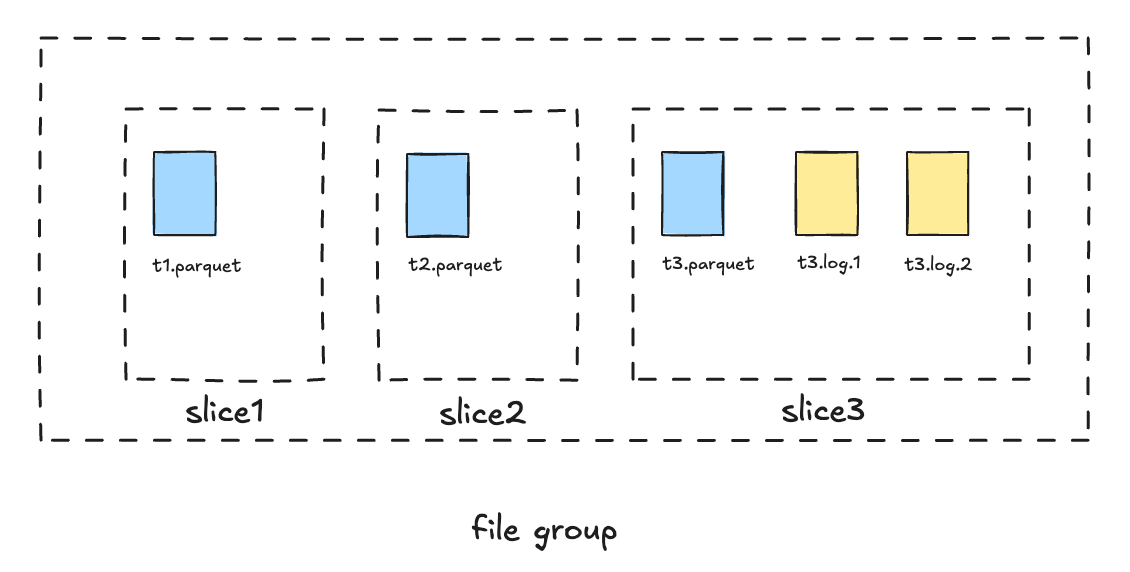

In concurrent write scenarios, the instant time naming convention of log files introduces certain limitations: as asynchronous compaction progresses, the base instant time can change. To ensure that writers can correctly determine the base instant time, the ordering between write commits and compaction scheduling must be enforced—meaning that compaction can only be scheduled when there are no ongoing write operations on the table. Otherwise, a log file might be written with an incorrect base instant time, potentially leading to data loss. As a result, compaction scheduling may block all writers in concurrency mode.

File Slicing Based on Completion Time

To address these issues, starting from version 1.0, Hudi introduced a new file slicing model based on a time interval defined by requested time and completion time. In release 1.x, each commit has two important time concepts: requested time and completion time. All generated timestamps are globally monotonically increasing. The timestamp in the log file name is no longer the base instant time, but rather the requested instant time of the write operation. During the file slicing process, Hudi looks up the completion time for each log file using its instant time and applies a new file slicing rule:

A log file belongs to the file slice with the maximum base requested time that is less than or equal to the log file's completion time. [5]

The new file slicing mechanism is more flexible, allowing compaction scheduling to be completely decoupled from the writer's ingestion process. Based on this mechanism, Hudi has also implemented powerful non-blocking concurrency control. For details, refer to RFC-66 [5].

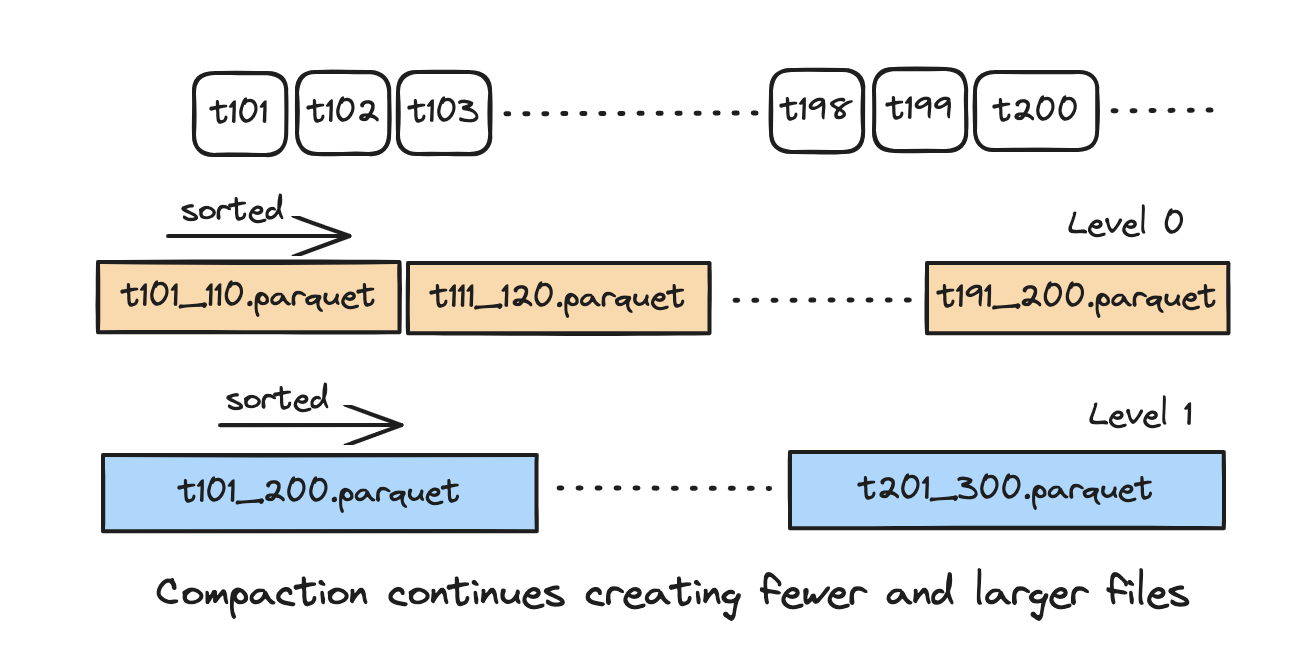

LSM Timeline

The new file slicing mechanism requires efficient querying of completion time based on instant time. Starting from version 1.x, Hudi re-implemented the archived timeline. The new archived timeline organizes its data files in an LSM-tree structure, enabling fast range-filtering queries based on instant time and supporting efficient data skipping. For more details, refer to [6].

TrueTime

A critical premise of Hudi's timeline is that the timestamp generated for instants must be globally monotonically increasing without any conflicts. However, maintaining time monotonicity in distributed transactions has long been a thorny problem due to:

- Clock skew: Physical clocks drift apart across machines.

- Network latency: Communication delays between data centers.

- Concurrent transactions: Difficulty in determining event ordering across regions.

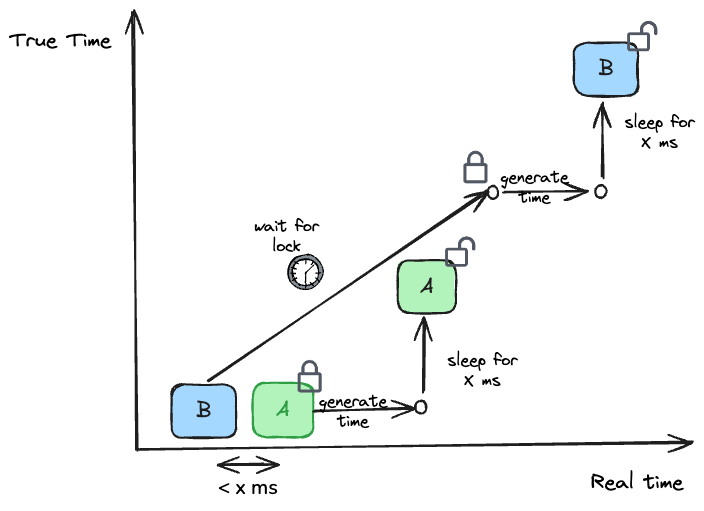

To solve this problem, Google Spanner's TrueTime [1] uses a globally synchronized clock with bounded uncertainty, allowing it to assign timestamps monotonically without conflicts. Similarly, Hudi introduced the TrueTime API [2] starting from the 1.0 release. There are generally two approaches to realize TrueTime semantics:

- A single shared time generator process or service, like Google Spanner's time service.

- Each process generates its own time and waits until time >= maximum expected clock drift across all processes, coordinated within a distributed lock.

Hudi's TrueTime API adopts the second approach: using a distributed lock to ensure only one process generates time at any given moment. The waiting mechanism ensures sufficient time passes so that the instant time is monotonically increasing globally.

Blocking Instant Time Generation for Flink Writers

For Flink streaming ingestion, each incremental transaction write can be roughly divided into the following stages:

- Writers write records into the in-memory buffer.

- When the buffer is full or a checkpoint is triggered, writers send a request to the coordinator for an instant time.

- Writers create data files based on the instant time and flush the data to storage.

- The coordinator commits the flushed files and metadata after receiving the ACK event for the successful checkpoint.

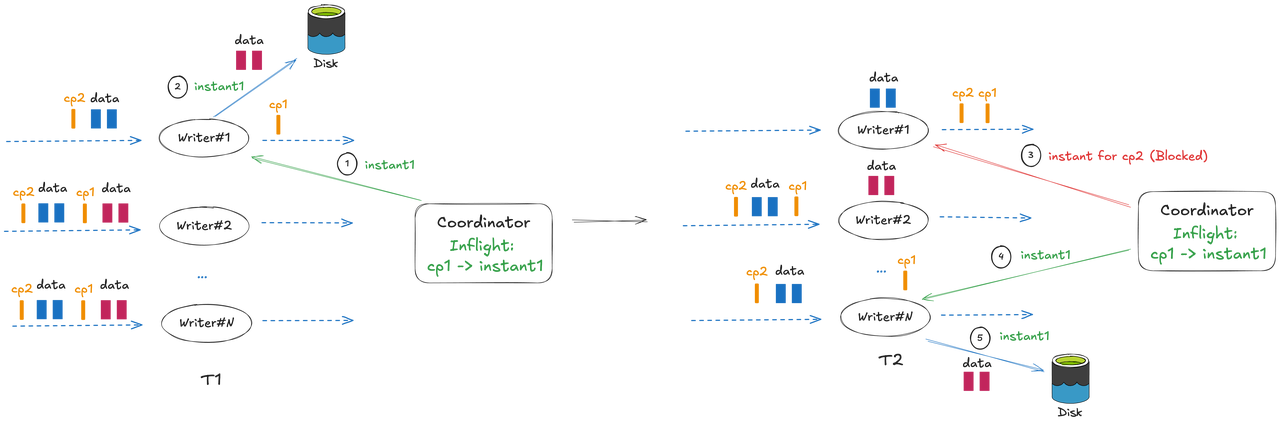

From Hudi's file slicing mechanism, we can see that the instant time is required before writers flush records into storage. Before 1.1, although the committing operation was performed asynchronously in the coordinator, the writer's request for a new instant would be blocked, because only after the previous instant is successfully committed can the coordinator create a new instant. Let's say a batch of records finished flushing with checkpoint ckp_1 in the writer at T1, and ckp_1 completed at time T2—the writer will be blocked in the time interval [T1, T2] (a new instant time is generated only after the ckp_1 completion event is handled and committed to the Hudi timeline). This blocking behavior ensures strict transaction ordering across multiple instants; however, it can lead to significant throughput fluctuations under large-scale workloads.

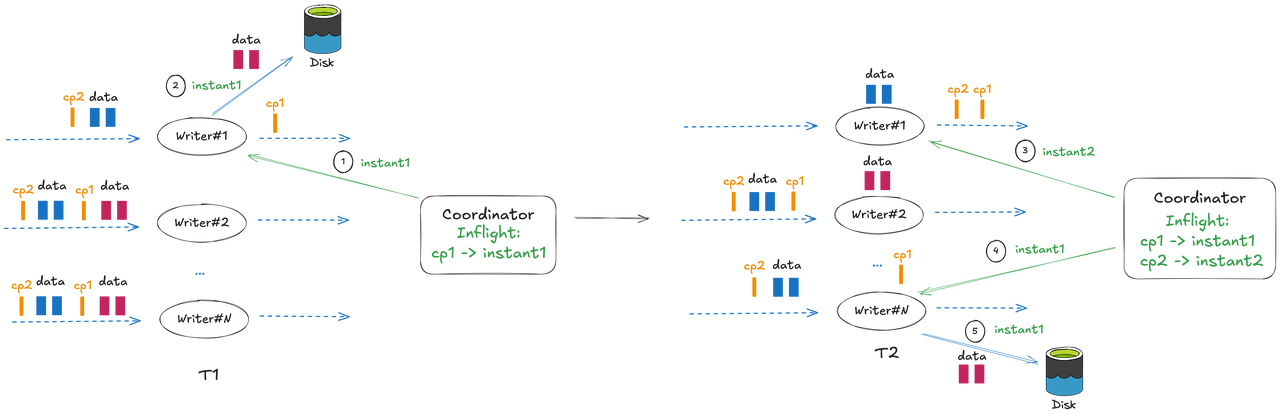

Async Instant Time Generation

To address throughput fluctuation caused by blocking instant generation, Hudi 1.1 introduces asynchronous instant generation for Flink writers. Using the aforementioned example, "async" means that before the previous instant is successfully committed to the timeline (during the time range [T1, T2]), the coordinator can create a new instant and return it to the writer for flushing a new batch of data. Thus, writers are no longer blocked during checkpoints, and the ingestion throughput will be more stable and smoother.

Overall write workflow:

- Writer: Requests instant time from the coordinator before flushing data:

- Data flushing may be triggered either by a checkpoint or by the buffer being full, so the request carries the last completed checkpoint ID, rather than the current checkpoint ID.

- For a request made at the initial startup of a task, if it's recovered from state, the checkpoint ID is fetched from the state; otherwise, it's set to -1.

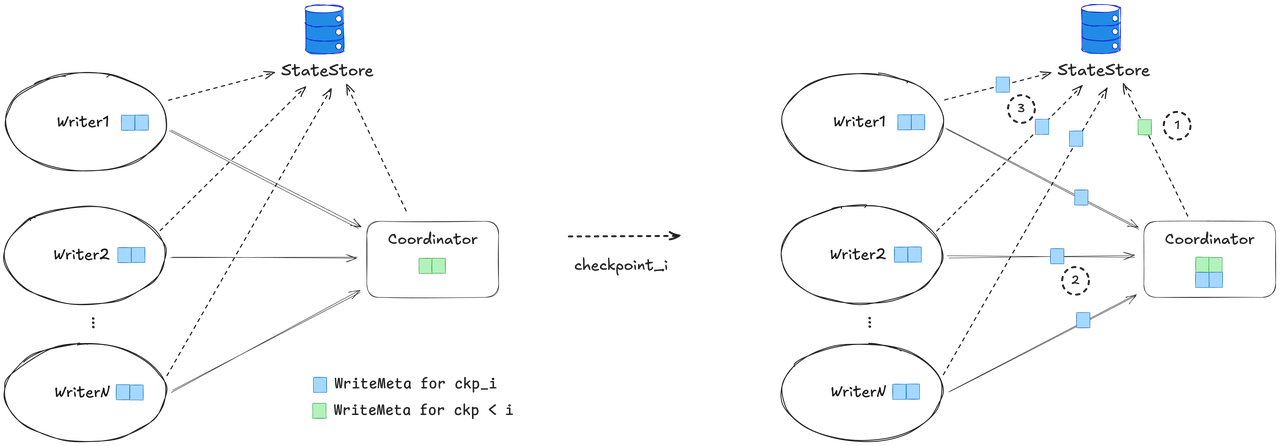

- Coordinator: Responsible for instant generation. Each checkpoint ID corresponds to an instant. The coordinator maintains the mapping in the WriteMeta buffer:

CheckpointID → { Instant → { Writer TaskID → Writer MetaEvent }}, where{Writer TaskID → Writer MetaEvent}is the mapping between each writer's parallel task ID and the file metadata written during the current checkpoint interval. Upon receiving an instant request from a writer:- If an instant corresponding to the checkpoint ID already exists in the WriteMeta buffer, the cached instant is returned directly.

- Otherwise, a new instant is generated, added to the WriteMeta buffer, and then returned to the writer.

- Writer: Completes data writing, generates data files, and sends the file metadata to the coordinator.

- Coordinator: Upon receiving the file metadata from a writer, updates the WriteMeta buffer:

- If there is no existing metadata for the current writer task in the buffer, the metadata is written directly into the cache.

- If metadata for the current writer task already exists (i.e., the writer has flushed multiple times), the metadata is merged and then the cache is updated.

- Coordinator: When the ACK event for a checkpoint (ID = n) is received, it starts serially and orderly committing the instants recorded in the WriteMeta buffer. The commit scope includes all instants corresponding to checkpoint IDs < n. Once committed successfully, the instants are removed from the buffer.

- Since Flink's checkpoint ACK mechanism does not guarantee that the coordinator will receive an ACK for every checkpoint, the commit logic follows Flink's Checkpoint Subsume Contract [4]: if the ACK for checkpoint

ckp_iis not received, its written metadata is subsumed into the pending metadata for the next checkpointckp_i+1, and will be committed once the ACK forckp_i+1is received.

- Since Flink's checkpoint ACK mechanism does not guarantee that the coordinator will receive an ACK for every checkpoint, the commit logic follows Flink's Checkpoint Subsume Contract [4]: if the ACK for checkpoint

WriteMeta Failover

Considering that the coordinator cannot guarantee receiving every checkpoint ACK event, the in-memory WriteMeta buffer needs to be persisted to Flink state to prevent data loss after a task failover.

When designing the snapshot for the WriteMeta buffer, the following points need to be considered:

- WriteMeta is initially stored in the writer's buffer. Only when a checkpoint is triggered or an eager flush occurs does the writer send the current WriteMeta to the coordinator.

- During checkpointing, the coordinator takes a snapshot first, followed by the writers' snapshot. At this point, the coordinator's cache does not yet include the WriteMeta for the current checkpoint interval.

Based on the above considerations, the WriteMeta snapshot process for checkpoint i is as follows:

- The coordinator first persists the WriteMeta for all checkpoint IDs < i to Flink state.

- The writer sends the WriteMeta generated during checkpoint i to the coordinator, awaiting commit.

- The writer cleans up the historical WriteMeta in state and persists the WriteMeta for checkpoint i to Flink state.

This approach of persisting the WriteMeta buffer ensures that metadata is not lost, while also preventing state bloat in the WriteMeta state.

Conclusion

The async instant time generation mechanism introduced in Hudi 1.1 is an important feature for improving the stability of Flink streaming ingestion. By eliminating the blocking dependency on the completion of the previous instant's commit, this mechanism solves the throughput fluctuation and backpressure problems under large-scale workloads. At the same time, it still maintains strong transactional guarantees and seamless integration with Flink's checkpoint semantics. This enhancement is fully backward-compatible and transparent to end users, enabling existing Flink streaming ingestion jobs to immediately benefit from smoother and more scalable ingestion with minimal changes. As the demands on real-time data lakes continue to grow, such innovations are key to building robust, high-performance lakehouse architectures.

References

[1] https://research.google/pubs/spanner-truetime-and-the-cap-theorem/

[2] https://hudi.apache.org/docs/next/timeline/#timeline-components

[3] https://github.com/apache/hudi/blob/master/rfc/rfc-66/rfc-66.md

[5] https://github.com/apache/hudi/blob/master/rfc/rfc-66/rfc-66.md

[6] https://hudi.apache.org/docs/next/timeline/#lsm-timeline-history